Twelve Years in the Making: An Audit of Irish Development Education Resources

Finding the 'Historically Possible': Contexts, Limits and Possibilities in Development Education

Abstract: The production of development education (DE) resources has been a key feature in the work of aid agencies, community organisations and international non-governmental organisations (INGOs) and received widespread support for more than two decades in Ireland. As part of its work programme in 2012, DevelopmentEducation.ie was commissioned by Irish Aid to undertake an audit of available DE resources as part of a broader agenda of creating an annotated online database of such resources. The resulting audit represents an initial attempt to begin cataloguing development education resources in Ireland - encountering some significant challenges while doing so, which are explored in the article below.

The main findings of the audit have been organised by education sector and theme across 236 identified DE resources. The main conclusions of the audit reveal that while many resources have been developed over the twelve year period there are significant gaps and opportunities for resource producers and NGOs to consider. There has been a significant increase in resource production in the past four or five years and the overall quality of resources has increased considerably in the past decade. While NGOs remain the key providers of DE resources, there has been a significant increase in those provided by educational and community structures and institutions.

Recommendations arising from the research include the pressing need for a central resource library/centre through which resources can be identified, accessed and purchased (as appropriate). As educational methods, approaches and ideas continue to change and develop there will always be a need for additional resources. It is hoped that this audit will assist with identifying and responding to priorities within this context and one of the constant issues that arose in the course of undertaking this audit was that of assessing the value and impact of resources in terms of their stated aims and objectives.

Key words: Development; Education; Audit; Resources; Ireland; Publications; Formal Sector; Non-formal Sector.

“Global issues are viewed as controversial and complex topics, and teachers often feel that their development education efforts are weakened by limited support and resources…

…Teachers often feel they do not possess the requisite resources, knowledge or expertise to translate their positive attitude towards education for global citizenship into classroom practice…

… Research on the scale and nature of development education provision in the adult and community education sector in particular are equivocal. As such, this is an area that warrants further investigation” (Extracts from Fiedler, Bryan and Bracken, 2011).

The production of development education (DE) resources has been a key feature in the work of aid agencies, community organisations and international non-governmental organisations (INGOs) and received widespread support for more than two decades in Ireland. It is often widely assumed as a result that the development education landscape is awash with teaching and learning resources, yet the extracts quoted above suggest otherwise; resource support exists but it is limited and difficult to access. As part of its work programme in 2012, DevelopmentEducation.ie was commissioned by Irish Aid to undertake an audit of available DE resources as part of a broader agenda of creating an annotated online database of such resources. As an online partnership project since 1999, the website was already operating as a reference point for development education in Ireland [1]. The fundamental purpose of undertaking the audit of resources was to research, list, describe and catalogue Irish produced DE resources published since 2000.

In the initial stages of research, it was envisaged by the website’s management committee that a number of challenges would be encountered which could potentially limit the research and mediate its impact including: defining what is (and, perhaps more importantly, what is not) a DE resource; obtaining copies of resources (due to their being no ‘central reference point’ for resources); and identifying ‘gaps’ in resource provision (deciding on what a gap is in the first place, is controversial) [2]. Recognising that definitions of development education are routinely contested, the following ‘working definition’ of development education was adopted by those undertaking the research for the purpose of the audit:

“Development education is directly concerned with the educational policies, strategies and processes around issues of human development, human rights and sustainability (and immediately related areas)” (Daly, Regan and Regan, 2013: 4).

Challenges in audit compilation

This audit represents an initial attempt to begin cataloguing development education resources in Ireland and, as such, it suffers from a series of significant challenges and must be interpreted in this light. There were three significant challenges: the timeframe for completion of the audit; defining a DE resource; and categorisation by theme and sector. It was necessary initially to restrict the terms of reference of the audit for very practical reasons – it was simply not possible to audit all resources given the timeframe available to us (the audit was undertaken between September and December 2012). As a result, there are many resources currently in use in Ireland which were not included or were produced by organisations and websites which have since closed down. In as much as it will be possible, these resources will be included in future audit updates on the site.

A second important challenge related to the debate about defining development education and related areas. For the purposes of this piece of work, a fairly restricted definition of a ‘DE resource’ was adopted (ibid). Resources profiling the work of agencies (both government bodies and non-governmental organisations) were included if they explicitly focused educationally on such work; this applies also to campaigning resources which had a strong educational strand. There is much to be gained educationally from promotional and campaigning materials once they are used interrogatively. Given that the majority of resources are produced by aid and development agencies, very many of these resources were primarily focused on fundraising and promotion and, as such, were excluded from the audit. As a general ‘rule of thumb’, promotional or campaigning resources which focused 50 percent or more of their content on educational concerns were included.

A third significant challenge in the compilation of the audit relates to the cataloguing of resources by theme and by sector. While it is necessary and useful to identify the dominant theme in a resource, many resources covered more than one or two key themes; in undertaking the audit, we have allocated a key theme to each resource (based on the degree of emphasis) but in most cases there was not an exclusive focus on one specific topic/theme. Equally, each resource was allocated a principal and subsidiary target group (based on the self-declared intent of publishers) but in many cases, the resource identified multiple potential users. As a result it is important to interpret the audit findings flexibly. Despite this, we would argue that the broad patterns identified in the audit remain accurate as regards both theme and sectoral focus.

Despite the challenges encountered in the compilation of the audit, it is hoped that this initial work will continue to be expanded and supplemented in coming years with the overall objective of establishing a national database of annotated resources which can be freely accessed and used.

Methodology

The methodology for the audit was agreed and overseen by members of the website’s management committee who collectively have considerable experience in development education practice, resource production and dissemination. Some aspects of the methodology are considered below.

Data collection

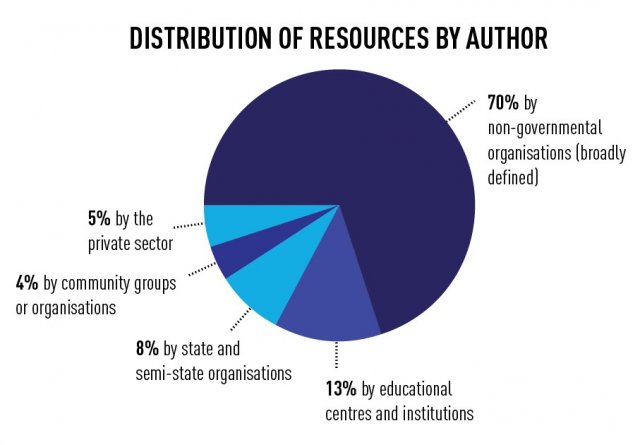

In order to collect the necessary data on each resource and to keep the information consistent, a standardised template was used and completed for each resource included in the audit. Initially, a pilot phase was carried out to test the template in practice and to discuss the strengths and weaknesses of the data collected. The template was subsequently reviewed based on the changing needs of the project and in consultation with the management committee. A statistical matrix was also designed to capture agreed qualitative indicators, organised by sector. It was also designed to preserve anonymity and establish an overall sense of the general state of DE resources in Ireland. Based on the information from the annotations, the matrix sought to extract the following from the resources included.

Table 1. Matrix of development education resources

Sourcing of resources

As there was no single online or offline reference point for DE resources in Ireland, it was agreed that a flexible approach to searching for and obtaining relevant resources would be necessary. The first 100+ resources were sourced directly from the DevelopmentEducation.ie online catalogue. The collection of data included the following methods:

- A systematic review of Irish DE, human rights and development websites, primarily Dóchas members (fifty sites), Irish Development Education Association (IDEA) members (50+ websites), One World Centres, Ubuntu and the Development and Intercultural Education (DICE) project. In addition, the websites and resources of all members of The Wheel were surveyed (10,000+) of which eventually thirty-seven member organisations were included.

- International development organisations’ websites (those with local offices in Ireland).

- A search for DE resources or databases produced by educators and/or students from formal education settings (curriculum development units [CDUs], local education centres, colleges, civic social and political education [CSPE] organisations, teachers’ associations etc.).

- Visits to libraries and the borrowing of resources directly from organisations (e.g. University College Dublin [UCD] development studies library).

- The websites of organisations and private publishing companies that do not explicitly identify with ‘development’ or ‘development education’ but which produce relevant resources, such as those for CSPE, education for sustainable development and human rights education.

- Discussions with a wide range of experienced DE practitioners and educators across the five sectors and with the website management committee.

Additionally, an audit ‘page’ was included on DevelopmentEducation.ie and individuals and organisations were encouraged to contribute details of additional resources that would be of value to users of the site.

Findings

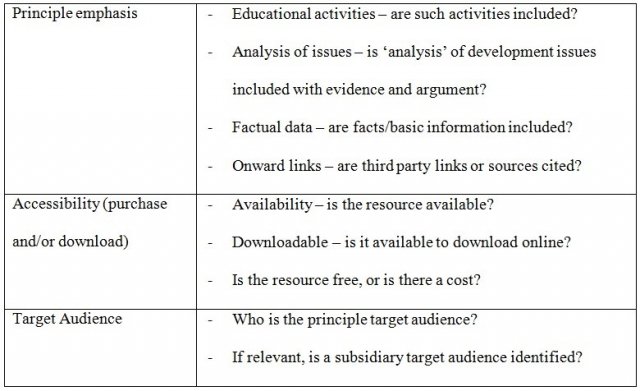

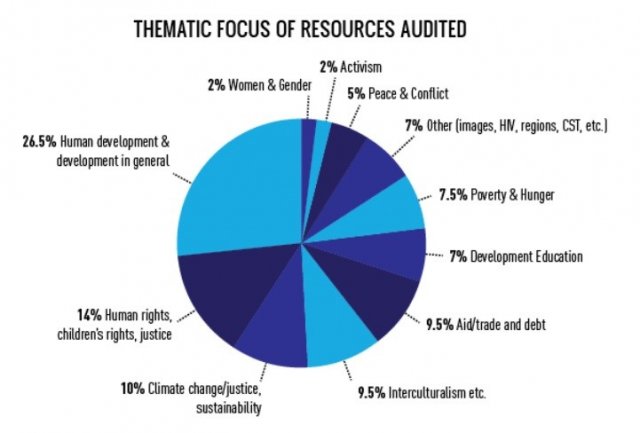

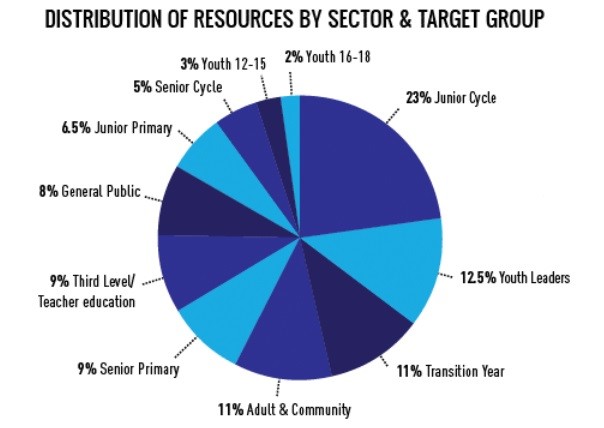

The main findings of the audit have been organised by education sector and theme across 236 identified DE resources [3]. The following pie charts provide snapshots of the associated trends.

Figure 1. Thematic focus of resources audited

Most notable thematic finding: only three development education resources have been produced in the last twelve years exclusively on ‘Women and Gender’.

Figure 2. Distribution of resources by sector and target group

Figure 3. Distribution of resources by author

In many cases, resources were produced jointly; this is especially the case with NGOs and educational institutions. Of the resources audited 40 percent received Irish Aid funding support (and its predecessor, Ireland Aid) and 60 percent derived from non-Irish funding. In terms of sectors, 69 percent were produced for non-formal education sectors and 31 percent for formal education sectors.

In terms of access and availability of resources, a central reference point and/or resource centre(s) is needed. As things stand, key resources are routinely difficult to locate and access, as was discovered in the research phase of the audit. Even with a team of three auditors working on the research for five months, resources were almost certainly missed.

Conclusions

The main conclusions of the audit reveal that while many resources have been developed over the twelve year period there are significant gaps and opportunities for resource producers and NGOs to consider. There has been a significant increase in resource production in the past four or five years and the overall quality of resources has increased considerably in the past decade. While NGOs remain the key providers of DE resources, there has been a significant increase in those provided by educational and community structures and institutions. The single most serviced sub-sector is junior cycle post-primary, accounting for 23 percent of all resources audited across eleven user sector groups, which stands in contrast to senior cycle as the most underserviced sector (notwithstanding youth leader resources also being used extensively by the 12-15 age group in secondary schools).

Additional findings include that the majority of resources are available online (80 percent) and for free (84 percent) but there is still significant demand and need for hard copy resources and there are ongoing limitations with digital resources, especially in the formal sector. While there is no shortage of ‘general’ resources, there are significant weaknesses and omissions in resource coverage sectorally and thematically. For example, there are limited sections as Gaeilge in some resources and the provision of entire resources as Gaeilge is effectively non-existent.

Recommendations arising from the research include the pressing need for a central resource library/centre through which resources can be identified, accessed and purchased (as appropriate). Such a reference point(s) is needed for the long-term agenda of DE as not all resources are available free online and it is unlikely that a central resource library, such as that on DevelopmentEducation.ie, would satisfy demand around resources. The challenges in confronting this need could be considered within the context of support for regional centres and DE libraries as a more practical outcome. It is also recommended that the database associated with this audit be maintained and expanded in the coming years; that it be made available online with a range of associated resources and supports and that producers of resources be encouraged to submit an annotation as new resources are developed. The database could include a far larger range and diversity of resources beyond those produced in Ireland and those formally recognised as DE resources.

As educational methods, approaches and ideas continue to change and develop there will always be a need for additional resources. Similarly, the need to update materials and analysis of development, environment and human rights issues will require the ongoing production of resources - as will responding to the gaps and opportunities identified in this audit. It is therefore recommended that resource production remains central to strategies and funding streams within Irish Aid and across the NGO sector. It is hoped that this audit will assist with identifying and responding to priorities within this context and one of the constant issues that arose in the course of undertaking this audit was that of assessing the value and impact of resources in terms of their stated aims and objectives. This is particularly the case with the many free resources as no cost is involved. It is recommended that research is initiated into assessing the actual use of resources and their impact among a diversity of sectors and users.

As there is continued evidence (from teachers in particular) of the need for and value of hard copy resources and as there are ongoing difficulties in accessing and downloading soft copy resources, it is recommended that both forms of resources continue to be funded. The audit has also highlighted the educational potential of ‘promotional’ and campaigning resources which continue to form a sizeable proportion of available ‘DE’ resources. It is recommended that both Irish Aid and the NGO sector review the educational components of such materials with a view to ensuring their greater relevance to DE and related areas overall [4]. It is also recommended that: all significant resources produced have an ISBN number; that funded resources remain available for a specified period as a condition of funding (at least five years); that resources remain accessible and visible on websites; and that, where feasible and appropriate, copies are made available to websites such as DevelopmentEducation.ie. As this audit was unable to undertake a review of major resources used at third level, it is recommended that such a review be initiated in order to better ensure the effective servicing of resources needed in that sector.

The challenge ahead and a DE resources agenda in Ireland

The general trend over the twelve year period covered by the audit highlighted the fact that a particular sector could expect to find anywhere between five and fifty-five resources produced for it although provision by sector varied hugely. Resource production by both sector and theme has been very uneven and often reflects the concerns and campaigns of the times where, for example the Millennium Development Goals, child labour or the war in Darfur, are chimed with the campaigns and agendas of governments and NGOs. While the changing context and areas of focus in development and human rights change and present new resource needs, there is also an ongoing need for core resources focusing on key cross-cutting themes and an additional need to ensure resource spread across sectors. This represents a very considerable challenge.

The findings and conclusions reached in the audit present many opportunities for educationalists, NGOs and resource producers in terms of which themes and sectors should receive greater focus in coming years. Many important themes remain relatively uncovered, as do key sectors – the overall implication is that there is a need for a more focused and contextualised approach and the audit should provide considerable assistance in this regard. The matrix of qualitative indicators served as a useful tool for assessing broad trends by sector and content, excusing the necessary crudeness of framing diverse resources in this manner. The implications of the matrix are important in terms of making professional judgements about balancing factual content, educational activities, analysis of issues and onward links. Where the audit was not in a position to make quality judgements of resources – separating ‘strong’ DE resources from ‘weak’ resources – it is nonetheless important for resource producers to be challenged in their consideration of the balance between development and human rights content, educational activities, curriculum and syllabus demands and user needs as early as possible in the resource production process.

To build on this initial piece of research, an annual update of the DE resources audit has been established as an ongoing baseline of data in order to assist and challenge prospective resource producers in Ireland. The update (taking on one of the recommendations of the audit) involves a partnership with Dóchas and IDEA to develop a set of supportive guidelines to be offered to the DE sector as a stimulus for resource planning and production [5]. Following a national consultation with the DE sector and interested bodies in April 2014, the finalised version of the supportive guidelines will be available from September 2014. Rather than closing down the possibilities for future resource production through the application of a set of ‘strict criteria’ or ‘rules’ to be followed (even by funders) it is essential to support heterogeneity and creativity. As the management committee of DevelopmentEducation.ie stated in September 2013:

“Many DE resources produced in Ireland to date are of the highest standard and are recognised internationally as such. All core DE resources should adhere to a basic set of agreed educational guidelines which reflect sound educational practice. However, they also need to adhere to sound development and human rights criteria and values, so curriculum and syllabi provide only one key dimension as regards resources.

It is also important to recognise that all groups have the right to produce resources and to seek to stimulate public discussion, debate and judgement even of conflicting and contrary views. Issue-based groups, campaigning groups, sectoral groups and political groups should be encouraged to produce sound educational resources – our democracy needs it. Which ones should receive state or voluntary organisation funding is a matter for those funders but it is vital that there is not ‘one’ agreed analysis or solution to world development and human rights issues and challenges” (DevelopmentEducation.ie, 2013)

Despite its limitations, it is hoped that the audit contributes to greater cohesion, relevance and quality as regards resource production in support of development education; the audit itself clearly highlights the ongoing need for such resources.

Notes

[1] The consortium of NGOs managing DevelopmentEducation.ie in 2012 comprised: Aidlink, Concern Worldwide, Irish Development Education Association (IDEA), National Youth Council of Ireland (NYCI), Self Help Africa, Trócaire and 80:20 Educating and Acting for a Better World. The website is co-financed by Irish Aid.

[2] Many studies in global education, development education and human rights education in Ireland have been produced in recent years yet remained sector specific, uneven and limited (such as over a two year period only). Such studies, however, were vital in informing the work of the audit, which include: Gallwey, S and Mollaghan, M (2008) Guide to Development Education Resources in Ireland 2006-2008, Limerick and Maynooth: Irish Aid and Trócaire; Gallwey, S and Mollaghan, M Guide to Development Education Resources in Ireland 2004-2005, Dublin and Maynooth: Development Cooperation Ireland and Trócaire; and Human Rights Education in Ireland: an overview (2011), a report by Irish Human Rights Commission, Dublin.

[3] A detailed breakdown based on sector with quantitative and qualitative characteristics can be found in the audit findings and we would recommend further reading in that regard. The audit has been made available online and in a downloadable version.

[4] This point expands on previous research and reports by Audrey Bryan and Meliosa Bracken (2011) in relation to assessing global citizenship teaching at post-primary level in Ireland as ‘obedient activism’ through to the shortfall in linking Civic, Social and Political Education (CSPE) concepts to action projects identified by the Chief Examiner in 2005 and 2009.

[5] Work updates, responses to the audit and information on the guidelines can be found at www.developmenteducation.ie/audit.

References

Bryan, A and Bracken, M (2011) Learning to Read the World: teaching and learning about Global Citizenship and International Development in Post-Primary Schools, Dublin: Irish Aid/Identikit.

DevelopmentEducation.ie (2013) Management Committee Consortium Response to the Audit, 20 September 2013, available: http://www.developmenteducation.ie/audit/responses-to-the-audit.html (accessed 24 January 2014).

DfID (1999) UK government's Department for International Development: Audit of development education resource provision in the UK, London: DfID.

Chief Examiner (2009) ‘Junior Certificate Examination: Civic, Social and Political Education: Common Level Chief Examiner’s Report’, State Examinations Commission, available: http://examinations.ie/archive/examiners_reports/JC_CSPE_2009.pdf (accessed 28 January 2014).

Daly, T, Regan, C and Regan C (2013) An Audit of Irish Development Education Resources, Report for www.DevelopmentEducation.ie, available: www.developmenteducation.ie/audit (accessed 24 January 2014).

Fiedler, M, Bryan, A and Bracken, M (2011) Mapping the Past, Charting the Future: A Review of the Irish Government’s Engagement with Development Education and a Meta-Analysis of Development Education Research in Ireland, Dublin: Irish Aid.

Gallwey, S and Mollaghan, M (2008) Guide to Development Education Resources in Ireland 2006-2008, Limerick and Maynooth: Irish Aid and Trócaire.

Tony Daly is an education consultant to 80:20 Educating and Acting for a Better World and writes for www.developmenteducation.ie. He has been directly engaged in human rights education, DE and political reform in Ireland and the UK for over a decade through projects such as Let’s Talk, The Convention on Modern Liberty and organisations such as 80:20, The Constitution Unit and the British Institute for Human Rights.

Ciara Regan is an education consultant to 80:20 Educating and Acting for a Better World. She has worked directly on thewww.developmenteducation.ie website for almost 4 years and has researched and published in the area of women and development in the context of HIV and AIDS in Zambia.